Since the last time that I wrote on transport resistance as a voltage loss mechanism in organic solar cells, due to low active layer conductivities, we have continued working on it.

While we learnt from our valued colleague Prof. Chang-Qi Ma that MoOx diffusion contributes strongly to fill factor losses by thermal degradation – they had published their convincing results in [Qin 2023], under our radar – we also understand better how to recognise and comprehend transport resistance losses.

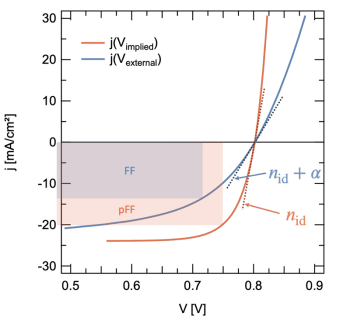

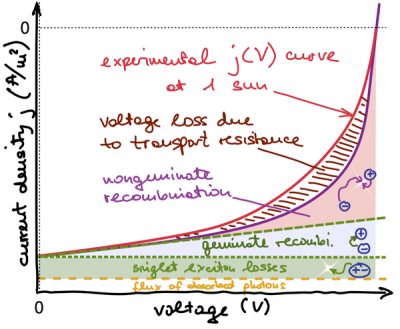

The simplest way to characterise transport resistance is to determine the difference between a normal current density–voltage curve under 1 sun, and the suns-Voc curve. The latter is the pair-wise combination of generation current density and open-circuit voltage that is giving one current density-voltage point per light intensity: doing this for a wide range of light-intensities results in a pseudo-JV curve. To compare this suns-Voc curve to the current density–voltage curve under 1 sun, it has to downshifted so that the open-circuit voltage of both curves coincide on one point: . The result could look like the scheme shown in the figure below. I have adapted this figure from Maria’s new publication on transport resistance losses in organic solar cells [Saladina 2025] (the title is Transport resistance strikes back: unveiling its impact on fill factor losses in organic solar cells ;-). The

curve (blue) is the normal JV curve under illumination, where

is the applied voltage. The down-shifted suns-Voc curve corresponds to the

(red); the implied voltage is the voltage without any series-resistance imposed drops. In other words, the externally applied voltage drops over the diode and all series resistances, the external series resistance as well as the transport resistance that comes from a low active layer (or transport layer) conductivity. The implied voltage, as measured by the open-circuit voltage (at zero current, where series resistances do not play a role), corresponds to the voltage without drops over series and transport resistance.

If a solar cell has a low active layer conductivity and is transport resistance limited, than the measurement of the suns-Voc curve to construct the

If a solar cell has a low active layer conductivity and is transport resistance limited, than the measurement of the suns-Voc curve to construct the -curve allows to evaluate the performance of that solar cell as if it did not have any transport resistance losses. One could also say: while the measured

curve is transport resistance limited, the pseudo-

curve corresponds to the case of infinite conductivity, but contains the same recombination as the measured curve.

Also indicated in the figure are two further figures-of-merit to distinguish the measured JV curve and the series resistance-free pseudo-JV curve: the slopes around the open circuit voltage (indicated in the figure by and

), and the fill factors – FF and the pseudo-FF. The FF is generally defined as fraction of the power at the maximum power point over the power given by short circuit current times open circuit voltage,

. The pseudo-FF does essentially the same, but for the series and transport resistance-free pseudo-jV curve. The normal FF (blueish) is not a measure of just recombination, but of recombination and series and transport resistance losses! The pseudo-FF (reddish) is due to only recombination losses. The difference between pFF and FF is, therefore, a measure of the transport resistance losses that the organic solar cell has.

The suns-Voc curve is used in the literature to determine the recombination ideality factor of solar cells. Even on the linear scale, the (inverse) slope of the corresponding -curve around Voc is given by the ideality factor

. The

curve has a slope which is given by the ideality factor and a figure-of-merit describing the transport resistance:

. It was introduced by [Neher 2016], and I state it here in its general form,

where the recombination current density equals at

, and

is the effective conductivity at open circuit.

is the active layer thickness, and

the thermal voltage. That means,

increases when the active layer conductivity decreases. Correspondingly, the slope of the jV curve under illumination (the

curve) becomes less steep and the FF goes down: these are the transport resistance losses.

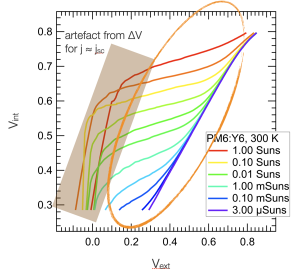

For a selection of devices that we characterised for [Saladina 2025], we show on the right-hand-side the impact of transport resistance on the fill factor. The upper limit of the FF (solid line) can be reached when the recombination ideality is unity and there are no transport resistance losses. The FF (open circles) is often much lower, but in modern devices such as PM6:Y6 it can exceed 75%. The pseudo-FF (filled circle), however, is much closer to the upper limit, and is due to the trap-assisted recombination found in organic solar cells, at ideality factors that are often larger than unity. All in all, the largest loss for the fill factor is the transport resistance loss, essentially the difference between the pseudo-FF and the FF, even for the (not shown here) record-efficiency organic solar cell devices! I believe it makes a lot of sense to quantify the transport resistance in all publications that present the performance organic solar cells, so to avoid drawing wrong conclusions – for instance, that a given low fill factor is due to recombination, when the FF loss is likely dominated by low active layer conductivities. This is even more important when looking at the losses of organic solar cells with thicker active layers.

For a selection of devices that we characterised for [Saladina 2025], we show on the right-hand-side the impact of transport resistance on the fill factor. The upper limit of the FF (solid line) can be reached when the recombination ideality is unity and there are no transport resistance losses. The FF (open circles) is often much lower, but in modern devices such as PM6:Y6 it can exceed 75%. The pseudo-FF (filled circle), however, is much closer to the upper limit, and is due to the trap-assisted recombination found in organic solar cells, at ideality factors that are often larger than unity. All in all, the largest loss for the fill factor is the transport resistance loss, essentially the difference between the pseudo-FF and the FF, even for the (not shown here) record-efficiency organic solar cell devices! I believe it makes a lot of sense to quantify the transport resistance in all publications that present the performance organic solar cells, so to avoid drawing wrong conclusions – for instance, that a given low fill factor is due to recombination, when the FF loss is likely dominated by low active layer conductivities. This is even more important when looking at the losses of organic solar cells with thicker active layers.

If you want to understand more about the transport resistance loss, I recommend (and self-advertise:) Maria’s paper, [Saladina 2025]. It contains information on how to predict the pseudo-FF just from the recombination ideality factor, how the conductivity of the active layer can be determined from the transport resistance, that is actually voltage dependent and not the best measure to describe the FF losses, how energetic disorder influences transport resistance, and how transport resistance losses can be minimised. As always, I am happy to hear your thoughts, in the comments or by email.

is reduced by

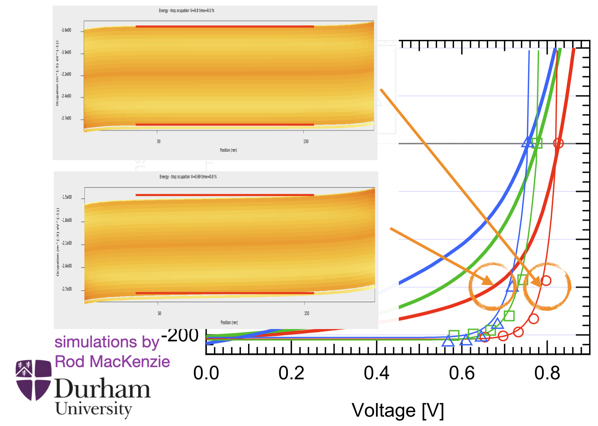

is reduced by  The upper left inset features the band bending of the transport resistance free case at a current–voltage point in the fourth quadrant of an illuminated solar cell,

The upper left inset features the band bending of the transport resistance free case at a current–voltage point in the fourth quadrant of an illuminated solar cell,  The ideal diagonal case where

The ideal diagonal case where